Chicago Tribune

Free at last from the weight of an immense fortune and momentarily without a woman to share his bed, Michael Butler is loping across an East Bank Club tennis court.

"Just look at him." says one of the club's firm and fit lovelies, somewhat older than were Audrey Hepburn or Candice Bergen when they were made to swoon by Butler. "He's a magnificent creature. Like some sort of colt playing in a field. Just delicious."

Always one to live exuberantly-some might say excessively-Butler has become something of a tennis nut. He talks about the game all the time and can be found playing it Monday and Thursday mornings at this sumptuously appointed palace of sweat-drenched exclusivity. He might be playing singles, as he does once in a while, but this day he is engaged in a friendly game of doubles with his pal Arnie Morton and two young pros.

"They are a lot of fun to play with," says Tom Wangelin, the club's head pro, who is often partnered with Butler. "They are very competitive and Arnie likes to take Michael's head off every time he gets a chance."

You can tell a lot about a person by the way he or she behaves on a tennis court, but you could watch Michael Butler play tennis for the next month worth of Mondays-his nearly 70-year-old joints willing-and you would not get a whiff of the wonder that has been his life.

"He's a pretty good player," says Morton, who also has had a colorful go of it, from running the Playboy Club empire to creating his own restaurants and clubs. "I've known him casually over the years, but we just started playing together about two years ago. We pretty much break even, though I'm a lot older than he is." The 74-year-old Morton pauses to laugh. "He's a sweet guy. He's just a plain, sweet, nice guy. There's nothing about him that would give you any hint about how rich he was or the life he lived."

In no specific order (for his life has been kaleidoscopic) and far from inclusive (for his life has been fully packed), Michael Butler dated Hepburn and Bergen and dozens of other beauties, gamboled around his godfather Tyrone Power's Hollywood manse, ran unsuccessfully for the Illinois legislature with the campaign slogan "Michael Butler likes polo, parties, and pop art-does that make him a bad guy?," produced the musical and the movie "Hair," lost a few million dollars, participated in a menage a trois or two, was an informal adviser to President John F. Kennedy, got high with Mick Jagger and horsed around with Prince Charles.

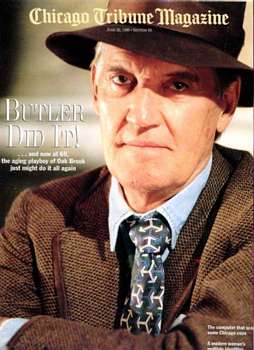

Those things and so many other adventures are now, mostly, mute memories. The movie-star good looks that so beguiled women (and men) are still relatively intact even if the image, polished by years of gossip columnists' elbow grease, has been tarnished a bit. Butler, even as he spends time making new deals and dreaming new dreams, often talks of the past. He doesn't dwell on it, but with a past so pretty, who could blame him for the occasional time trip?

He says of his childhood, spent in horse-jumping, fox-hunting, polo playing west suburban luxury, "It was Camelot," and you could search the list of prominent city and North Shore families-the Swifts, McCormicks, Palmers, Armours, Blairs, Fields-before realizing that the only apt comparison to the Butler family Is in that gang of East Coast athletic, overachieving indulgers known as the Kennedys.

Symbolically, there is a picture of JFK sitting among a field of framed family pictures on a small table in Butler's apartment. It was snapped by Butler during a 1958 sailing jaunt off the southern coast of France.

"Jack was a marvelous man and I loved Jackie, though she hated me at first, thinking that I was leading Jack astray," he says. "Later we became very close, once she realized it was Jack who was leading me astray."'

It is difficult to imagine anyone leading Butler astray. As if in testament to-or editorial admiration of-the breadth of his personality, one of the many thick files of news clippings in the Tribune library that chronicle Butler's busy life is labeled "Industrialist, Millionaire, Sportsman, Playboy."

That's no hyperbole-and it omits "Producer," the activity for which Butler will likely be remembered.

If Michael Butler had never been born, surely someone would have had to invent him He is the sort of person who would have fascinated F. Scott Fitzgerald. Indeed, circa the soggy spring of Michael Butler's life in 1996, one could not help but recall the words With which Fitzgerald ended his masterpiece "The Great Gatsby": "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

I'm not so good on dates," Butler says. "But I am very good on the people and events of my life."

He is dressed in tennis whites, shockingly simple in this color-splashed Agassied-age. He moves across the court with a certain amount of grace. His serve isn't much beyond accurate but he hits strong forehands. He has a solid old man's game with one unconventional twist: switching his racket from right to left hand when hitting overheads.

"My right arm Is shorter than my left arm," he says. "It is the result of a horseback riding accident when I was 7. It broke and never healed properly. So, that's why I switch hands. One has to make certain accommodations to life."

This is the age of accommodations.

No longer able to play polo, his life's sporting passion, because, Butler says, "I'm too old and it's too expensive," he took up tennis two years ago. No longer a multimillionaire, Butler makes do by setting up deals for and between wealthy friends. No longer the owner of five large houses around the world, he lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Chicago. No longer the leader of a pack that once included polo players, movie stars, rock musicians, politicians, royalty and other nefarious sorts, he is now part of other people's entourages.

After a life in the limelight-star-studded and star-crossed-Butler drifted into the ignominious shadow of a personal bankruptcy six years ago. More clouds were cast by an auction (six framed pictures of Mick for sale!) that accompanied the bankruptcy; by a garage sale five years ago that ended his live-in relationship with Oak Brook, the posh community that had been created and developed by his father, Paul, and of which he was the most famous and flamboyant resident.

"It's like the end of an era for Oak Brook," said Butler family friend Joan Wegner at the time. "The Butlers did more for Oak Brook than anyone in Oak Brook. It's done without too much comment, and that's a very sad thing. For Michael to slip away was sad."

But being forced to "slip away" did not make Butler a broken man, as it has others-Nixon, who placed Butler on his infamous enemies list, comes to mind. Butler may be bankrupt, but he's neither broken nor broke. He has merely downsized.

"The yoke had been lifted," he says, popping vitamin pills along with a piece of fish at the East Bank Club restaurant. "I now have a tremendous amount of free time. I used to have five houses to take care of and now I only have the one apartment. There is a liberating feeling, a freedom in that"

Freedom's just another word for a small loft apartment in a building on the banks of the Chicago River. It is a place cluttered with artifacts and art. A huge silver cup, a polo trophy, serves as a planter. On the large bed sits a small Teddy bear. Out the windows, which face west, is a gritty cityscape. There are no trees, green hills or pristine polo fields like those that formed the window views for most of Butler's life. There are gray buildings and a quilt of railroad tracks.

"It's like having a toy train set," he says.

And he always has liked his toys.

He was presented with a special one on Christmas in 1936. It was his first polo pony, tied to the back of the horse-drawn sled used to convey members of the Butler family from the Hinsdale train station to the family farm, called Natoma.

It was a present from his father. In that year and in that place there were four of them: Paul; Michael and his siblings, Frank, who was two years younger, and Jorie, who was 6. Their mother, the former Marjorie Stresenreuter, had, after her divorce from Paul, shared custody of the children for a few years. Then, after an ugly battle in the courts and in the press, she relinquished full custody to Paul.

The Butlers-father and children-lived in a rambling white farm- house, surrounded by the gently rolling countryside first seen by Michael's great-great-grandfather, Oliver Morris Butler, who started a paper mill on the Fox River in St. Charles in the 1830s. His brother, Julius Wales Butler, opened a paper merchant firm on Chicago's State Street in the 1840s, and his son, Frank, purchased property in Hinsdale and built the Natoma dairy farm in 1898-and other houses nearby.

Paul Butler was raised in that house and, after a reluctant interlude in the 1920s living in town on Astor Street, moved his family to the then pastoral area.

"Dad was;. .I adored him," says Michael Butler. "He was incredibly autocratic in a wonderful way. My memory is probably a lot better than some of my feelings at the time, because I remember mostly the good things: the way of life in Oak Brook. It was mind-boggling."

Paul Butler was also, to hear some tell it, something of a tyrant.

"One of the quietest, iciest people I've ever known," says a longtime family acquaintance. "I do not remember one time he ever showed the children any outward form of affection or love."

Paul was also very rich, which made him-except when occupied by

another short marriage in the 1940s-the area's perennial

"most eligible bachelor." It is some indication of the

tensions that may have existed within the family-the

overpowering presence of Paul-that his eldest son in his late

teens changed his name from Paul Jr. to Michael.

Michael first worked for the family paper business in the Chicago area at 17, and as a 22-year-old trainee set a company sales record before transferring to the European division.

There he became involved in business deals renovating a Middle Eastern railroad and operating coal washeries in India. Through those ventures and his polo playing connections, his circle expanded widely into the worlds of the very wealthy, nobility, movie stars, heads of state and tycoons.

In 1954, Hollywood connections-his godfather really was Tyrone Power-allowed him to meet and marry Mary Schenck, the daughter of Nicholas Schenck, a former president of MGM Studios, and an actress/singer who used the stage name Marti Stevens. He was later married to socialite Mary Robinson Boyer for a couple of years; and in 1962 to socialite Loyce Stinson Hand, with whom he had his only child, a boy named Adam, born in 1964, and a messy divorce that dragged on from the couple's separation in 1965 to 1971.

Between matrimonial engagements, he dated.

"That was the only thing that ever upset me about Michael," says his sister Jorie. "He would introduce these marvelous looking women and say to me, 'You should try and pattern yourself after this Miss So-and-So.' And there I was, in my blue jeans and riding boots, my hair pulled back."

One of these marvelous looking women was Audrey Hepburn.

"She was fabulous," Michael recalls. "But she was too sophisticated for me. I regret getting her involved in the New York production of a play called 'Ondine.' That's where she met [future husband for a time] Mel Ferrer. He became her Svengali. Not a nice man."

While Michael dabbled in business and theater-the family invested in such hits as "West Side Story" and "Kismet"-his father began transforming a quiet slice of west suburban landscape into his vision of nirvana.

Paul Butler had inherited land and had been buying other real estate-neighboring farms, acre by acre-for 30 years, eventually owning nearly 5,000 acres. After founding the Oak Brook Polo Club in the '20s, he oversaw the laying of bridle paths and the clearing of fox-hunting fields. He developed what he called a sports core, a 500-acre area of 13 polo fields, a golf course, riding trails and an airstrip.

In 1958, when his properties were threatened with annexation from the surrounding suburbs of Hinsdale and Elmhurst, he incorporated the village as Oak Brook and began to develop the land. He influenced many of his wealthy business pals to venture west, where they could build gleaming corporate structures and move into lavish homes. He influenced politicians to move the location of the East-West Tollway farther north, so as not to interfere with his plans.

"He was a

developer-as-visionary," says a former business associate.

"He could be a bastard to deal with, but he got things

done. He was able to blend it all together-the office buildings,

deluxe homes, retail shopping center and vast recreational

spaces-into one of the most remarkable, high quality suburbs in

the country."

The pastoral lifestyle Michael Butler had known as a child was vanishing when he returned here to live in the mid-1960s. And the business also was transformed. Paul Butler sold the paper company. He merged Butler Aviation with two other companies, took that company public and cashed out. He entered into a partnership with Arizona developer Del Webb. As father developed, son became increasingly interested in politics.

Michael had served as an informal adviser to JFK on Middle Eastern and Indian matters and was asked by Bobby Kennedy to help Gov. Otto Kerner's 1964 reelection campaign. Kerner won and, ever appreciative, gave Butler posts on the Illinois Sports Council and the Organization For the Economic Development of Illinois; he was the founding chancellor of the Lincoln Academy and the commissioner of the Port of Chicago. All this fueled Butler's run two years later as a Democrat for the Illinois Senate in the 39th District (DuPage County), which had not elected a Democrat since the Civil War. He lost by a 2-1 margin to Jack T. Knuepfer of Elmhurst.

What to do next?

Rich and handsome is not a career, and Butler was not as passionate about real estate as was his father.

While contemplating a run against Illinois' gravel-voiced senator, Everett Dirksen, Michael was in New York on business. Sitting in one of the many clubs to which he belonged, he was thumbing through a newspaper when his eye fell on an advertisement for a play being presented by Joseph Papp's New York Shakespeare Festival: "Hair (The American Tribal Love Rock Musical)."

"I thought it was about American Indians," he says now. "I went to see the play and was blown away. It was the strongest anti-war statement I had ever seen. I met with Papp and asked him to bring the show to Illinois, but he wasn't into that"

But Papp was into forming a partnership with Butler, who decided to give up politics for good.

After a Papp-Butler co-production at a New York disco called the Cheetah bombed, Butler bought Papp out, reworked the show's book, added the famous nude scene and wrote a more upbeat ending.

"Hair" opened at the Biltmore Theater on Broadway in April, 1968, and it blew a lot of people away. It would eventually run for 1,742 performances, spawn 29 other productions in 17 countries.

Butler was an attentive and involved producer, visiting and helping oversee almost every city's production.

"I felt responsible for each tribe," he says.

A few times he appeared on stage, once in LA painted from head to foot in silver and wearing an Indian headdress, and a couple of times he joined the San Francisco cast for the show's nude scene.

"It was no big deal, the nude scene in San Francisco," he says. "I was living with two of the cast members."

Flush with "Hair" cash-it's estimated that Butler made about $10 million from the show-he careened through the 1970s. There were parties and more parties; polo and more polo; Candice Bergen and other lovelies; private planes and a chauffeur-driven Rolls.

"He was like a rock 'n' roll star, a counterculture king," says an old friend. "But for every person who really liked Michael, who genuinely shared his hippie mentality, there were others just trying to catch a free ride on this ongoing party."

Butler spent most of his time living and entertaining in a mansion on 150 acres outside of London. He felt a special kinship to Great Britain, where he was able to trace his French-Anglo ancestry back to the Norman conquests.

There and in the U.S., he backed all sorts of ventures. Some, like the play "Lenny," worked. Many others-discos, roller rinks, a professional soccer team, rock bands-did not. He donated hundreds Of thousands of dollars to liberal causes.

He thought he had another "Hair" on his hands with a show called "Reggae," which he described at the time as a "Caribbean version of' South Pacific' with religious overtones," but when it opened on Broadway in 1980, it got hammered by the critics and closed after a brief run. That, coupled with the savage reception of the release of the long delayed movie version of "Hair," compelled Butler to retreat to Oak Brook, where, he says, "I thought I would be able to lick my wounds."

Instead of peace, he got pandemonium.

The moment It started is precise: 9:11 p.m. June 24, 1981. That is when Paul Butler was fatally struck by a car. It was the day after his 89th birthday and he was standing on the Salt Creek Bridge, aiming his camera at the evening sky. He was only a couple of hundred yards from the house.

As often happens in families when a lot of money is left in tangled circumstances-in this case so something in the neighborhood of $80-million-contentiousness becomes commonplace and lawyers salivate.

Battles erupted between the Oak Brook Park District and the Butler family. Between McDonald's, the area's premiere corporate resident, and the Butler family. But most emotionally and financially exhausting were the more than decade long skirmishes among Paul Butler's three principal heirs.

"It was litigation hell," says Michael.

When it was all over there was very little left. "The lawyers made out like the bandits they are," says a family friend. "The problem was that Paul left an estate that couldn't be unraveled by the best minds."

Michael blames his bankruptcy not only on the family fractiousness but on his own limitations as a money manager, ill-advised entertainment ventures and a weakened real estate market

Frank-never much for the media but known to have sported an earring before that became a fashion commonplace and who once dressed a pet dog in a full-length fur coat-now lives in Florida. Michael doesn't talk to him and is reluctant to talk about him.

Jorie also lives in Florida. She and her husband, Geoffrey Kent, operate Abercrombie & Kent, a leading African safari outfit, and she operates Design Horizons International, a graphic design firm with offices in Chicago and Florida.

She is a friendly woman, a leading conservationist. And she loves her brother.

"I am very fond of him," she says. "I love him dearly. Why? Why for his sense of humor, his spirit, his integrity, his devotion to his friends. Whenever I'm with Michael. I consider it my prime time."

She rarely visits Oak Brook, content with memories of her first polo pony and of looking at the stars and moon with her father.

"I miss what Oak Brook was, but I'm glad Dad's dream is as it is now," she says. "Daddy was very, very quiet. But he lived a remarkable life-from the horse and buggy to men walking on the moon, There's a lot of Dad in Michael-his sense of humor, his curiosity."

For all of those, and there are hundreds, who like Mike, others don't

"He's just a spoiled, rich kid," says one who has had business dealings with Michael. "He expected to have his way because he was Paul Butler's kid, but he doesn't have the old man's, smarts or style or toughness."

"All that peace and love crap he spouts," says someone from the same social circles. "He's a guy who had one big success and a lot of duds. It's rather pathetic that he clings to all that hippie stuff"

But Butler likes it that way. Long ago he was dubbed by the press "the hippie millionaire" and he says now, "Everybody's got to get a tag; I'm no longer a millionaire. But I guess I'm a hippie at heart"'

His conversation is peppered with the vernacular.

"Cool," he says frequently. "Peace and love," he says at the end of phone calls.

"There is a certain naiveté to Michael," says a friend. "I'd hate for him to hear this, but he's too trusting sometimes, too 'love and peace.' For all his worldliness, he's quite childlike."

His sister Jorie says that Michael "might be too trusting, but that's what makes him such a good friend, a good person."

One of the first people to send a note to Michael offering comfort and aid after the news of his bankruptcy hit the news was Prince Charles.

"From a financial viewpoint it was tough," Butler says. "I moved to a lifestyle that isn't one-tenth what it once was. But I learned how many really good friends I had.

"Worst of all, though, I put the family reputation in jeopardy, and I think I let [my son] Adam down."

Adam Butler was once a professional polo player and manager of polo clubs here and in Mexico and Canada. He now sells insurance for Met Life and is happily married to a woman named Michelle.

"I don't feel Dad let me down," he says. "Maybe he didn't discuss financial details as fully as I might have liked-I was shocked to find out how leveraged we were-but I love and respect my dad.

"He always treated me like a human being. He was very open with me. In a family with this sort of stature, it would be easy to lose Intimacy. We never did. He's a great man to me.

Adam is the only Butler who still lives in the suburb that his grandfather grew. "Most of the people who live here now don't really know about my dad or grandfather. There's no real burden for me here," he says. "And you sure can't beat the location."

Michael Butler is happy in town, where he spends much of his days as what he calls a "rainmaker," setting up deals among those in his worldwide network of friends. He is the manager of two family trusts and a few other "minor investments." Since his bankruptcy, he's studied for and received futures brokering and real estate licenses. He's become a "Star Trek" fan ("Love the new one, hate the old one"), has more time, to read and become something of a computer geek, with installments of his memoirs appearing on the Internet. (Butler is at http://www.orlok.com.)

"The one thing I don't have is a live-in partner," he says. "And I've always had a live-in partner."

He made his return to the public eye earlier this year when he produced "Pope Joan" at the Mercury Theatre. The musical, which had won the 1995 Joseph Jefferson Award for best new work in its inaugural performance at Bailiwick Repertory, tells the imagined rise and fall of the only female pontiff.

In March, during the last week of the play's shortened run, Butler was still stinging from its reception, saying, "1t is a good production. People like it. I was astonished by the ugliness of the criticism, the personal attacks."

But two months after the play closed he was cooler, saying, "The show was oversold and underproduced. It was still actually a workshop production."

Michael Cullen, a longtime Chicago producer, owner of a popular bar/restaurant and one of the owners of the Mercury Theatre met Butler during preparations for "Pope Joan."

"Of course, I knew of him. And I admired him. 'Hair' .was truly a generational show," Cullen says. "To produce a show like that, that's strong stuff. And he was a high roller. I followed his life in the society pages.

"He's definitely a gentle man. I think he's got a very good heart, he put a lot into the play. I'm sorry it didn't work out for him."

Undaunted, Butler believes in "Pope Joan." He traveled to New York in late May to discuss a possible production there, though its likely to be mounted first in Los Angeles or London.

He is also involved with the Amsterdam-based DogTroep theater company, a hit a few years ago at the Chicago International Theatre Festival. He is constantly reading scripts, talking deals..

"I always like to have a lot of things going," he says, proudly mentioning the name of his production and development company, Orlok.

And always there is 'Hair."

He produced a flashy revival at The Vic theater in 1988, and though the critical reception was good, ticket sales were flat and the show closed early, further increasing his financial woes at the time.

For the last couple of years Butler has been thinking of remounting the show. After;; seeing a "fantastic" version at Cal State University-Fullerton, he made a deal to mount that school's Pacific Musical Theatre's "Hair" at the Athenaeum Theatre in August. The timing is not coincidental.

"I think it would be a perfect show for the Democratic convention," he says. "It will help remind people of that time."

Butler needs no reminding.

In 1968 Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin came to him and asked that he give a benefit performance of "Hair" for the Yippies.

"Why do you want the money?" asked Butler.

"We want to train in martial arts," said Hoffman.

"Why?" asked Butler. "During the convention, we want to be able to meet 'The Man' and do in the 'pigs' when we go to the Democratic convention in Chicago. We will parade and camp out in Grant Park and you know the 'pigs' will never let us do that."

Butler arranged a meeting with Mayor Richard J. Daley.

"I told him that the city should smother the Yippies with tender loving kindness, "he says. "He decided to go a different way. And what did we get? Richard Nixon."

And Butler got a note from Hoffman: "Your stables with the polo ponies should all burn down." Butler sighs at the memory.

"Nothing can touch that time," he says. "We really believed this could be a great world. That we could change the world.

"I think there is a tremendous curiosity about the '60s and many people are still groping to understand what happened. `Flower power didn't tell people how to run the machinery once we got our hands on it.

"So many things need to be

done. We have to tie into the pursuit of peace and love, convert

from the materialistic to the humanistic." He means this.

You can see it in his eyes and hear it in his voice-animated,

passionate. And perhaps it's easy for him to sing the peace and

love song. He has a deal in the works that, he says, "might

some time this summer allow me to be forever sheltered from

want."

But he seems, to want for very little. If you could have heard him on the phone a couple of weeks ago, you would have heard him arrange a date With a stunning British woman to see a play in Amsterdam on August 1. You would have heard him discuss a possible horse back trip with some wealthy friends through Chile and Argentina.

"I am as happy and free as I've ever been. I have learned a lot about myself and other people in the last few years. What do I want? I want one of these days to spend some time in the Himalayas. I've never been there. I think I might like it," he says, looking out at a city still glistening from a midday rain, the clouds parting a bit to the west just enough to let the sun shine through.